The need

End-stage kidney disease

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is the final stage of chronic kidney disease, often resulting from a combination of underlying conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and genetic predisposition. At this stage, the kidneys lose their ability to effectively filter excess fluids, electrolytes, and metabolic waste, leading to toxicity, severe systemic complications, and increased mortality risk.

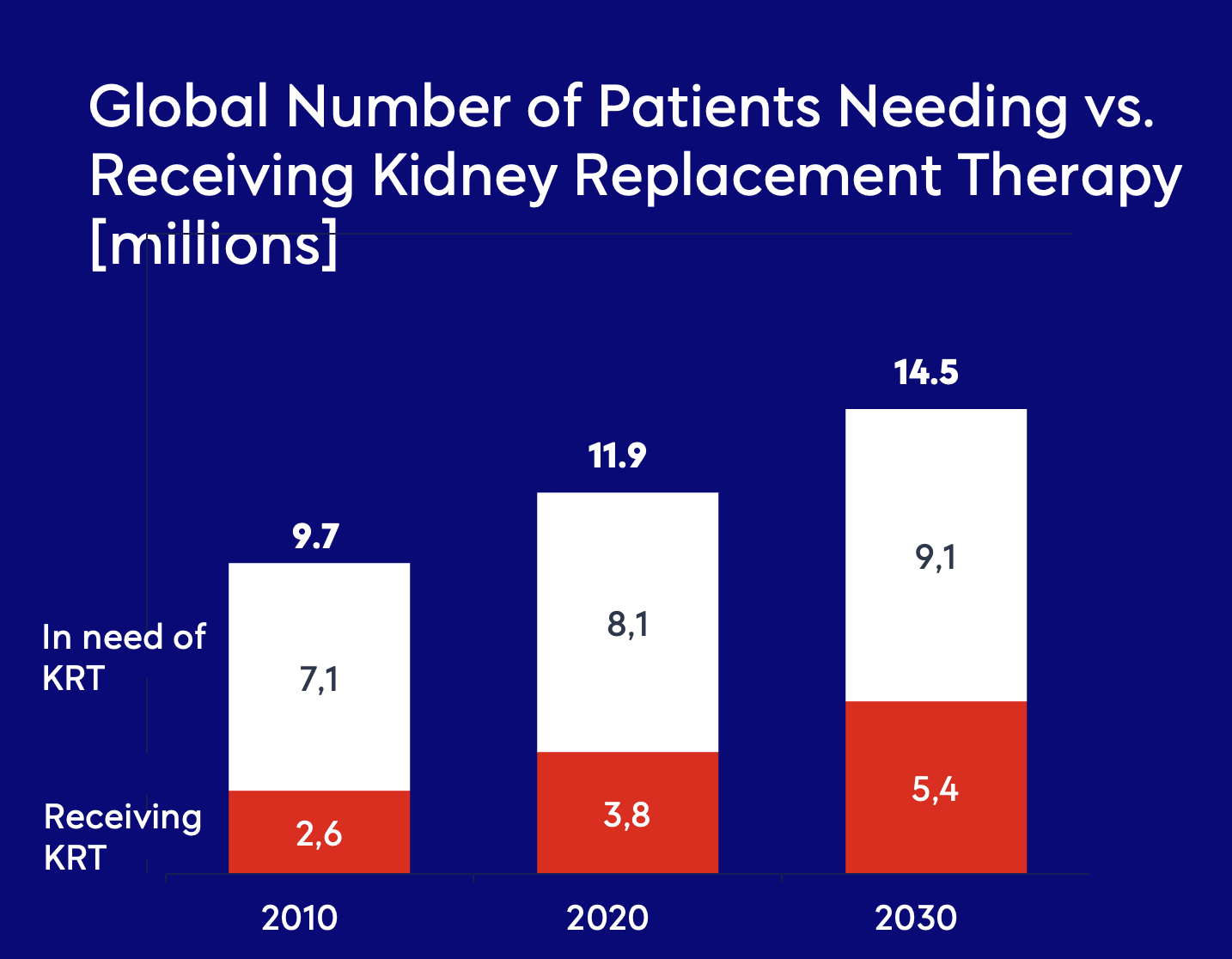

To sustain life, patients with ESKD require kidney replacement therapy to compensate for lost renal function. However, due to a severe shortage of donor kidneys for transplantation, the majority of patients rely on hemodialysis—a process that artificially removes waste and excess fluids from the bloodstream—to prevent life-threatening complications.

Vascular access for hemodialysis

Hemodialysis is the most commonly used modality for kidney replacement therapy, utilizing an external filtration system—the dialyzer, or “artificial kidney”—to remove metabolic waste, excess electrolytes, and fluid from the bloodstream. A high-flow vascular access site is essential for effective dialysis, requiring a minimum blood flow of 600 mL/min to ensure adequate circulation through the extracorporeal circuit.

The preferred method for achieving this high flow is the surgical creation of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF), in which a direct connection is established between a major artery and vein in the arm. The pressure gradient between the artery and vein facilitates the development of a low-resistance, high-flow conduit, optimizing access for dialysis. AVF remains the gold standard for vascular access due to its superior long-term patency and lower complication rates.

When native vessels are unsuitable, an arteriovenous graft (AVG) is used, incorporating a synthetic conduit, commonly made of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), to bridge the artery and vein. In cases requiring immediate or temporary access, a central venous catheter (CVC) is often placed, though it is associated with a higher risk of infection, thrombosis, and inadequate blood flow.

Complications of current treatment

The high-flow vascular access site required for hemodialysis frequently causes serious complications, such as:

Loss of access patency: Luminal narrowing (stenosis) of the venous outflow tract near the AVF, ultimately leading to AVF thrombosis, is the main limiting factor for the durability of the AVF. Maintaining vascular access requires frequent (on average 1.5 times per year) follow-up surgery

Heart failure: A continuously functioning arteriovenous fistula (AVF) leads to a reduction in systemic vascular resistance, triggering a state of hyperdynamic circulation. This results in a compensatory increase in cardiac output, placing an additional hemodynamic burden on the heart, contributing to ventricular remodeling, volume overload, and ultimately, heart failure progression for these vulnerable patients

Compression time & risk of bleeding: Due to high pressure and flow, patients need to compress for at least 10 minutes after dialysis to avoid bleeding. When the patient returns home the risk of bleeding may persist since the blood flow remains high in the vein

Steal syndrome: Peripheral ischemia of the forearm and hand as a result of “stealing” arterial blood flow into the AVF

Aneurysms: The high turbulent blood flow causes dilatation of the vein of the AVF, which increases the risk of aneurysm formation in the draining vein